Now, this is not a new method of training or learning...this is what the players used to do before computers became strong enough to make better moves than most players. And perhaps many people still do. I know many who do what I did though...right after their game, they look at points where they were confused and fire up the engine to see what they should have played or to confirm their decisions during the game.

In this post, I'm going to discuss a few of the benefits and limitations of analyzing by hand and also how one might maximize its effectiveness.

Benefits

1. Analyzing by hand helps practice skills of analysis used during games. These skills include calculation of variations, evaluation of resulting positions, and selecting candidate moves. Even if you are moving pieces on the board (instead of doing it all in your head), you still need to evaluate and organize the variations you come up with. If you do this with focus and self-awareness, I believe you will become more efficient and effective at it.

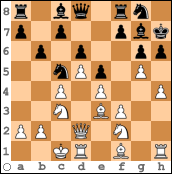

2. You will more likely remember what you discover in your analysis than if you didn't because of the engagement and emotions involved in your work. To use an easy example, consider the following position.

This is a well-known checkmating pattern that I and many others can instantly spot: 1...Nf2+ 2.Kg1 Nh3+ 3.Kh1 Qg1+! 4.Rxg1 Nf2#

I first discovered this pattern in a problem from a tactics book. I can spot this pattern, or at least consider it now whenever the appropriate elements of it are in place (e.g. the positioning of queen and knight, the weakness on f2, etc.) as opposed to if I had just been shown this without figuring it out myself.

The remembering I think is partly due to the emotional aspect (e.g. the satisfaction or frustration you may feel) of your involvement with the analysis.

3. Analyzing by hand helps to develop understanding of positions. When you fire up your chess engine to figure out a move, the computer is not telling you why the move is the best move. However, when you work thoroughly through various variations, seeing why "obvious" moves you might make work or don't work, and then taking a step back and looking at your work as a whole, you begin to have true understanding of the chess position you were analyzing. I believe this ability improves itself with practice. The key is the willingness to work at it.

Now, there are a few limitations of this type of work:

1. It takes a time. Analyzing by hand will take more time to find the answers than if you used a computer chess engine. This is a situation where the benefits far outweigh the cost. This is of course if your purpose is not only to find the best moves in the position, but also to better yourself as a player.

This reminds me of something I learned from GM Gregory Serper. I had taken a lesson with him years ago, when we both lived in Cleveland. We only had one lesson, but it made a big impact on me. He told me how as one of his assignments when he was studying under Kasparov was to correct the analysis in one of Kasparov's books. He said, "and I didn't cheat by using the computer." He said this took him several months (or a couple years...I forget exactly) but by the time he was finished his strength had grown tremendously to where he is now a Grandmaster (although I believe he is currently retired from active play). Note that the assignment wasn't just to correct the analysis but to gain experience and knowledge from the process of doing it!

2. You may not find the right answer or best moves. This is certainly a limitation and here is a couple suggestions to help with that. First, set a time limit to how much time you will spend on a position (perhaps depending on complexity of the position and whether you think you are on the right track). After your time is up and you feel you're spinning your wheels (which to some extent is a good thing), you can then either go to a stronger player or chess engine and see what you may have missed.

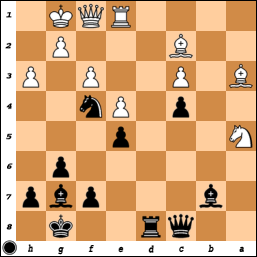

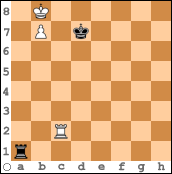

For example, consider the fundamental Lucena Position:

When I first saw this type of position in my games, I tried analyzing for about an hour and actually figured it out. However, unless you figure out the "bridge building" technique, all of your analysis may be frustrating. I think a little frustration is good for learning, but a lot may be counterproductive. So if you don't know the answer to this position, then try analyzing for say 15 minutes before reading the solution.

The solution is 1.Rd2+ Ke7 2.Rd4! (building a bridge for the White king to clear a path for the pawn) 2...Ke6 3.Kc7 Rc1+ 4.Kb6 Rb1+ 5.Kc6 Rc1+ 6.Kb5 Rb1+ 7.Rb4 and White's pawn will queen. Black's best resistance is 5...Rb2 (waiting patiently behind the pawn) 6.Re4+ (pushing the king further away) 6...Kf5 7.Rc4 and the king will escort the pawn to the promotion square.

Once you have learned the pattern, then it's with you forever (with some occasional review). So by using chess engines and reference sources after you've tried analyzing it yourself, you get the benefit of learning important patterns as well as the practice of analyzing. And as I mentioned in an above point, you will most likely remember the pattern more deeply by doing the previous analysis.

3. Analyzing by hand can be difficult. This is a definite limitation, but playing chess well is not easy, which is why it is worthwhile. I won't belabor this point, but I guess we all need to ask ourselves (and any answer is valid) whether or not putting in the effort and time (analyzing by hand) is worth the benefits (getting better at chess).

Conclusion

Now before I conclude this post, I do want to mention that this advice is aimed at mid-level amateurs like myself (I was going to put a level range, but instead I will describe what I mean). Players who are beginners may not have many "tools" in the toolbox for super-deep analysis, so may want to limit the time they allot to a smaller amount before seeking help from a stronger player, reference, or chess engine (in that order). Strong players who have developed their analysis skills to a high level may want to use the chess engines for assistance earlier in the process so they can cover more ground faster. Obviously, it is up to each player to determine what level is right for them.

In summary, I think analyzing by hand is a great way to practice and learn chess. Those who have the tendency to fire up Fritz, Junior, Rybka, or Crafty right after their games may want to consider taking a little time to analyze by hand first. The use of computer analysis after this is done may enhance your work. I hope that if you don't already, you may try this and not only experience the benefits of this type of training, but also the joy of analyzing and solving interesting positions.